About a week back, I had gone to Coimbatore to present a brief lecture on green IT, at the VLB Janakiammal College of Engineering, on the outskirts of the city.

The college itself is located in a pleasant setting, almost amid the hills, so I must say it was a wonderful experience being there.

.

As I was about to leave the college after the talk, I noticed that far and away, there were a few wind mills turning in the wind. As I had a few hours before my bus taking me back to Chennai was due, I and my colleague Ramesh quickly decided to make a visit to the wind farm. On enquiry, we figured the wind farm was farther than we thought – about 60 Kms away, next to the town of Pollachi, in a small location called Andhiyur. But we had already made up our minds to go.

After about 75 minutes of a car ride, and just a few minutes after Pollachi, we were at Anthiyur (well, I was told the location was Anthiyur, but on a Google check, it appears that Anthiyur was a bit of distance away from where we were…anyway, let’s say it was very close to Pollachi, which we had just crossed before we landed up at the wind farms).

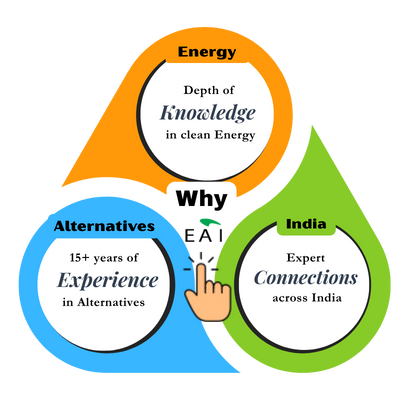

Net Zero by Narsi

Insights and interactions on climate action by Narasimhan Santhanam, Director - EAI

View full playlistIt was almost dusk when we arrived the location, and you could immediately see a dramatic scene wherever you looked. The place was swarming with wind mills.

.

The photograph above does not do true justice to the grandeur of the location, for two reasons: One, I am a lousy photographer and two, the light was almost going out at that time and all I had was a mobile phone camera to shoot. You still could however see the great number of windmills chumming along…

I spent the next 45 minutes doing a lot many interesting things. Firstly, I wished to simply stand under these huge machines and “feel them”. Here’s one of those majestic ones, 80 meters tall, 1.6 MW in capacity (owned by Vestas) and standing tall and proud

.

I was fortunate to find an engineer living in a small tent next to the wind turbine you see above (OK, tent is a grand word. It was a small hut). The chap was nice enough to answer my questions.

But before that, I thought I should walk in the middle of the windmills. That showed me how these wind mills were actually set in the middle of farmlands. This is one of the advantages of wind farms, as opposed to the solar farms that require the entire land surface and thus make it difficult to grow crops (solar farms however could be perfect fit as rooftops for large areas such as parking lots etc where the stuff underneath does not require sunshine!). The wind turbine itself occupied very little area (on the ground, the feet of the wind mill tower must have occupied only about 5 sq m. The transformers and the breaker circuit kept next to it would have occupied another 30-50 sq m. That’s it. Not bad for a machine that can generate about 2.2 million units of electricity per year. A large part of the land otherwise could be used to grow crops, and that in fact was what I saw out there, and just to get a feel for it, I walked across some of the farmland. Let me say it was a nice feeling to see energy producing machines peacefully co-existing with food producing crops (I was reminded of the constant food-vs-fuel debate we have in our office when it came to biofuels).

.

One funny thing I found while I stood there in the middle of tens of such fine machines, with dusk falling fast and a cool, positive feeling all around me, was that though most of the machines were located reasonably close to each other (less than half a Km between each), a few of the wind mills were turning, while most others were not. One would have assumed that with such proximity, either all would turn or none would.

Time to go back for a chat with the engineer. I asked him about the curious fact of some wind mills not turning while a few others were. I can’t say I fully understood his explanation, but it appeared to do something with the fact that the wind speeds at specific altitudes could differ significantly even within such short distances. I also wanted to know about the splendid looking machine in front of me – he informed me it was a 1.6 MW NEG Micon turbine (now owned by Vestas; it was merged with Vestas in 2004).

He further went on to tell me that Vestas alone had about 250 turbines located there, varying from 750 kW to 2.5 MW machines. Further, he said Gamesa was putting up a number of turbines (850 kW) at a nearby location. A bit of quick math told me that I was looking at over 250 MW, perhaps close to 500 MW of wind power capacity installed in this small region alone. Wooof, India’s total installed capacity is under 12 GW, so we are talking about close to 5% of the entire country’s wind energy capacity located in such a small region. Not bad at all.

Sometimes, you simply have to be there to feel it. Standing in front of these turbines and seeing them occupying such a small footprint for the amount of electricity they generate, I was wondering how these compare with biomass-based power generation. To give you an idea, a 1.6 MW power station (all right, such small power stations do not exist, this is just to compare apples to apples) will generate about 11,000 MWh of electricity per year and will require a minimum of 6000 T of dry biomass (at 500 Kg of biomass = 1 Mwh of electricity). Being extremely generous about biomass productivity, let’s take 50 T of dry biomass per hectare per year. So, that would require 100 hectares of land to produce enough biomass to run a 1.6 MW power plant. Now, let’s say these plants have a capacity factor of about 80% vis a vis 25% for wind farms, so for equivalent output, you will require only about 100*(25/80) or about 30 hectares. That’s still a heck of a lot. The wind machine in front of me was occupying a small fraction of that area, and required much less operational efforts than would growing energy crops require. Oh well, none of these inferences were new to me, these have been analyzed threadbare world over, it’s just being there and seeing it, you start thinking about these once more.

Now that I was standing right next to the turbine, I was curious to know the type of maintenance that was required. It appears that they do periodic maintenance (once in a month?) by changing the oil filters and applying grease to the turbines. This they do by going to the top of the wind mill (a staircase is located inside the tower was what I was told).

As for the breakers located next to the turbine, they were located to break the circuit when there is a lack of power supply from the grid (Oh OK, actually it is the turbine that supplies power to the grid, but the turbine requires an initial power from the grid while starting…the breaker is to ensure that the turbine doesn’t get affected when it requires power and there is no power from the grid).

Another interesting aspect I noticed was the concept of a feeder line. Essentially, the concept of the feeder line is that, starting with one turbine, the electricity line takes the power to the next turbine and combines the output of that turbine as well. This “feeder” process continues for seven turbines before the combined power is fed to a substation.

I spent a few more minutes with the engineer. I’m not sure what his background his, possibly a diploma, but he seems to live in a small hut right next to the turbine and I presume he takes care of many of the Vestas turbines around that area. He was a bright lad – had all the numbers and data on his fingertips.

Thus it was I spent an interesting hour at a wind farm. I had seen wind farms before, but I never had stayed at one of them for so long. I look forward to visiting such farms once more and stand below these admirable machines generating clean power.

Our specialty focus areas include

Our specialty focus areas include

ZEV India Partnership – Driving Truck Electrification through Collaboration

ZEV India Partnership – Driving Truck Electrification through Collaboration