It’s not everyday that we read of Indian scientists making breakthroughs in solar PV, so it was interesting for me to read this article on an Indian company coming up with some innovative solar PV tech.

For A.K. Barua, professor emeritus at the 130-year-old Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science in Kolkata, commercialization took 32 long years, but eventually it helped his industry partner HHV Solar Technologies Pvt. Ltd break into the international league where companies sell turnkey production lines for thin film solar cells. Only a few equipment suppliers operate in this space, led by Applied Materials Inc., headquartered in California, and Oerlikon Solar of Swiss industrial group Oerlikon. If domestic users take to HHV’s technology, the competition could get very tough for existing vendors, said Kotwal. Why?

Even if novel, innovations made by Indian scientists have traditionally hit upon economic and socio-political barriers to success. However, on overcoming these, India’s indigenous technologies have always been cheaper.

At $12 million (around Rs54.7 crore) for the plant, his new technology has cut the hardware cost from the prevailing rate for setting up such a unit of about $30 million. “That’s very competitive. High capital cost is a major factor in the adoption of thin film technology,” said Amol Kotwal, deputy director, energy and power system, South Asia, Middle East and North Africa, Frost and Sullivan (F&S).

For a long time, India didn’t pay attention to solar technology, Barua said. His own lab, despite being an early starter, faced intermittent funding shortages. Crystalline silicon, with about 15% efficiency, has gained some market share but since temperatures in many parts of the country go very high, thin film is more suitable in those regions, he said. “Beyond a point, a one degree rise in temperature leads to half a percent drop in crystalline cell efficiency.”

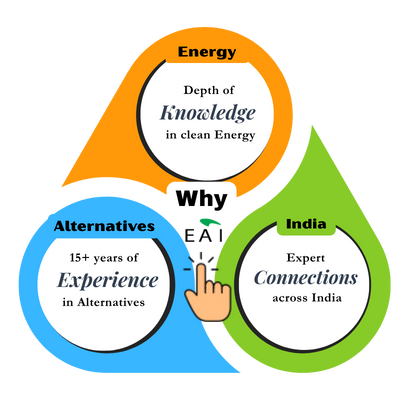

Net Zero by Narsi

Insights and interactions on climate action by Narasimhan Santhanam, Director - EAI

View full playlistAt the core of Barua’s team’s work lies the “plasma enhanced chemical vapour deposition” technology, which is a method of depositing silicon on glass to turn it into an electricity-generating module. “It’s a proud moment for us to have completely indigenized the technology development as well as the equipment,” said C.S. Solanki, professor of energy science and engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai. He says it comes at the right time as this is the focus of the NSM. However, “unless the cost difference (between crystalline and thin film) is substantial, say $1 per watt, thin film adoption will be low,” he cautioned.

The actual cost-benefit ratio, Sakhamuri said, is not efficiency dependent. “Thin film is 35% cheaper than crystalline. For a given 100W module, thin cells produce more power than crystalline as they react to a wider spectrum of sunlight.”

HHV Solar set up a 10MW demonstration production facility in Dabaspet, 50km from Bangalore, and in so doing, became the first Indian company to have developed the technology as well as the equipment for setting up a production facility for thin film solar photovoltaic (SPV) modules.

Moreover, HHV has also signed a deal with Solar Source Corp., a Canadian renewable energy holding company, to establish Canada’s first thin film amorphous silicon solar panel manufacturing plant.

“We are in serious negotiations with some Indian companies and intend to close at least four deals very soon,” said Prasanth Sakhamuri, managing director of HHV Solar, a holding company of Hind High Vacuum Co. Pvt. Ltd.

Solar technology is entering the third generation, but first-generation crystalline silicon solar cells dominate the market, accounting for 87.3% of the global 6.3 gigawatts of solar photovoltaic installations, according to F&S estimates for 2009. Thin solar cells constitute the second generation, where amorphous silicon leads the pack. The latter, though cheaper, lighter and flexible, is less efficient than crystalline cells.

A global race is on to increase the efficiency of thin cells, from the present 6.75-7% to 10% and beyond. From its research stable, supported by the ministry of new and renewable energy, HHV plans to roll out modules with 8% efficiency within a year. Efficiency refers to the rate at which solar power is converted into usable energy.

“So far there was no market in India. Companies exported most of their modules. The solar mission has created the critical local demand,” said Madhu Atre, president of Applied Materials India. The feed-in tariff of Rs18.44/kWh under the National Solar Mission (NSM) is a definitive step forward, he adds. The feed-in tariff is a premium, cost-based compensation rate offered to producers of renewable energy.

Our specialty focus areas include

Our specialty focus areas include