The Barefoot College, an Indian institution, embraces a novel and refreshing development ethos. Shunning the patriarchal mentality typical among organizations working with the rural poor, this place empowers rural people by teaching the technical skills to serve their own development needs.

Set in a the small village of Tilonia in a semi-desert part of Rajasthan, one of India’s poorest states, the college is a place of informal, unstructured learning where village women in colorful saris sit concentrating on configuring solar-powered electrity circuit boards and soldering radio parts.

This college is no ordinary place of learning.

The reach of their work extends not only to the parched, isolated villages of India, Bhutan, Pakistan and Afghanistan, but to communities in some 21 different African countries.

Laxman Singh has worked at the college for the past 20 years and is himself of a so-called lower caste origin. He explained the college’s focus on women by exposing them to technologies that aid development and raise living standards in ways that are harmless to the fragile environments where so many live.

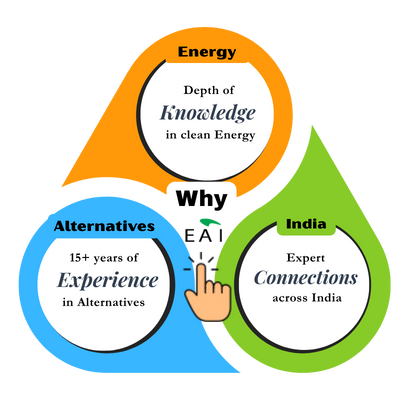

Net Zero by Narsi

Insights and interactions on climate action by Narasimhan Santhanam, Director - EAI

View full playlistThe college itself is a showcase for some of these innovations: solar panels and parabolic mirror-reflector cookers are ubiquitous. Various tanks and channels around the grounds, and conduits on the buildings, form an elaborate system of rainwater collection and storage inspired by traditional practices.

The women who learn such techniques here, Mr. Singh said, will bring their education and skills back home to their villages and put them to work for the betterment of the community. “Women can change everything,” he says.

That is the idea behind the Barefoot Solar Engineers initiative: community women travel to the college to learn how to solar-electrify their villages. They spend six months at the college learning the intricacies of configuring circuit boards and hooking up panels, before returning home equipped with enough materials and spare parts to be in business for the next 5 to 10 years.

Households pay fees equivalent to what they’d otherwise have to spend on kerosene and candles — thus ensuring sustainability of the program and a livelihood for the barefoot engineer.

Helen Nchenge, 43, from Cameroon is one of 21 women from seven different African countries studying at the college. she says: “This is going to change peoples’ lives, because the village has been living in darkness”.

Source:

Our specialty focus areas include

Our specialty focus areas include

ZEV India Partnership – Driving Truck Electrification through Collaboration

ZEV India Partnership – Driving Truck Electrification through Collaboration